I believe there is a lot more I should learn more about this topic, and I have never been directly involved in a clinical trial.

Nevertheless, these are my current thoughts about the possibility of what might be interesting about providing having generics directly enter the clinic/market through non-profit organizations (admittedly largely influenced by my experiences in genomics, which may be less relevant for some other applications):

Possible Advantages to Patients / Physicians:

- [data sharing / diagnostic transparency] Maximize public / accessible information available in order to help specialists make "best guesses" about how to proceed with available information

- I don't believe that sale of access to raw genetic data should be allowed

- Specialists / physicians should have access to maximal information to help guide decision making process

- I think it would be nice if some information was completely public, such as population-level data from Color Genomics (even though re-processing data can probably change some variant calls, and this company isn't a non-profit).

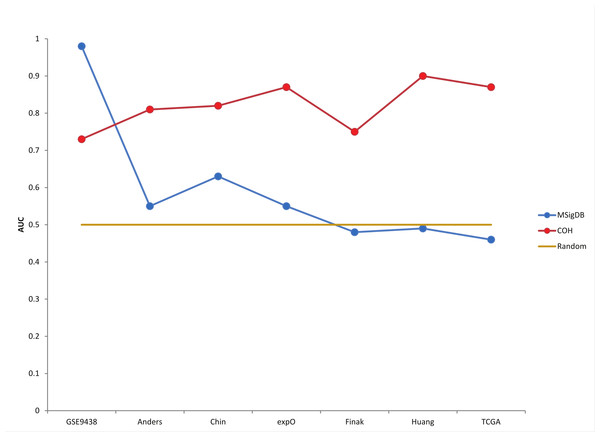

- In general, I think it is important not to place too much emphasis on any one study. As an example of how that could skew a true estimate of risk, I think there is a useful barplot in this paper. While over-fitting is not always the explanation, that can be a factor and I think I have a figure in this blog post that I hope can help explain that concern.

- I am most familiar with this in the context of genomics (which would be for research or diagnostic purposes). However, I have submitted several FDA MedWatch reports (again, mostly for diagnostics), and there is still a need for surveillance of therapeutics after they have entered the market.

- [data availability for patient autonomy] Making sure patients have access to all data generated from their samples

- Having access to your raw data should also help you be capable of getting specialized interpretation as a second opinion.

- I also think self-reporting (with the ability of the patient to provide raw data) may help with regulation (or at least setting realistic expectations about efficacy / side-effects).

- I think it may help if there was more judicious use of advertising.

- Namely, I worry that some advertisements can give a false sense of confidence in the interpretation of results. For example, I posted this draft a little early because of 23andMe's marketing of travel destinations based upon ancestry, which I don't approve of (although I support other overall goals for 23andMe).

- That said, I think it can be useful when digital advertisements allow you to comment on them, kind of like a mini self-reporting system.

- If we are talking about a therapy (rather than a diagnostic), I would expect this should also decrease costs (and is what I most commonly think of when I hear the word "generic"). Otherwise, I am mostly talking about experience with the exchange of information, often dependent upon sequencing/genotyping from another company (like an Illumina sequencer) that frequently makes use of open-source software (or analysis where unnecessarily complexity may sometimes even cause problems).

If this makes production via non-profit preferable, then perhaps a penalty for not meeting the above requirements could be an organization could risk losing it's non-profit status. Otherwise, I am primarily concerned that the above conditions are met (at least in genomics), and I am just curious if being a non-profit might help in sustainable accomplishing that goal (although I lack knowledge on many of the accounting and legal details, and I don't have experience running a non-profit or for-profit organization).

Possible Advantages to Providers?

- Assuming expectations are defined clearly and appropriately, participation in "on-going research" may improve understanding (and forgiveness) when there are many unknowns (and possibility even limits to what can be known with high-confidence in the immediate future)?

- I called this "Decreased liability?" in an earlier version of this post, but I have gotten feedback that makes me question whether this is precisely what I want to describe.

- If I understand things correctly (and it is possible to show that precisely defining all costs to society is difficult), it seems like forgoing royalties / extra profits in exchange for limited liability (kind of like open-source software, as I understand it) could be appealing in certain situations.

- Strictly speaking, I see a warning of limited liability within the 23andMe Terms of Service (if you actually read through it). However, I also know that I am entitled to $40 off purchasing another kit, because of the KCC settlement. So, I would expect actually enforcing limited liability would be easier for a non-profit (if their profits were limited to begin with, it is harder to get extra money from them).

- So, even though I believe the concept of limited liability applies in other circumstances, I think public opinion of the organization is important in terms of being patient and understanding when difficulties are encountered.

- Decreased or lack of taxes paid by non-profit?

- I think part of the point of having a non-profit is making the primary focus something other than money. However, I think this link describes some financial advantages and disadvantages to starting a non-profit.

- There was one person who raised concerns that non-products can't produce products (at least if I understood them correctly). While I admit that I don't fully understand the tax law, I think connections to research, education, and/or "public goods" qualify for the examples that I am thinking of. So, I can't tell if any rules need to be changed, but I found some summaries on-line that make me think things may currently be OK (such as here and here).

- At least from my end, this page says what I thought of when I was saying something should be offered by a non-profit: "Charitable nonprofits typically have these elements: 1) a mission that focuses on activities that benefit society and whose goal is not primarily for profit, 2) public ownership where no person owns shares of the corporation or interests in its property, 3) income that must never be distributed to any owners but recycled back into the nonprofit corporation's public benefit mission and activities....In contrast, a for-profit business seeks to generate income for its founders and employees. Profits, made by sales of products or services, measure the success of for-profit companies and those profits are shared with owners, employees, and shareholders."

I also originally had a bullet point for "If profits are limited, what about refunds?". However, I decided to place less emphasis on that point after additional feedback. For example, I recently purchased an upgrade from 23andMe (for their V5 chip, from their V3 chip). I noticed that I had to acknowledge that the purchase was non-refundable when I purchased the upgrade. If it is possible (and/or tactful) for the company to provide refunds, then I think there are disadvantages to this style of not providing refunds. However, this also made me think twice about how such an interaction would look if you were hesitant to give a refund because your profits were limited (and you have things like salary caps). Most importantly, both non-profits and for-profits have to make sure they are not compromising safety (or unfairly representing their product).

Also, to be fair, I think of "ownership" to be different when you talk about "owning" a pet versus "owning" a product to sell. However, I think the concept of responsibility for the former is important, and it is also definitely possible that there are misconceptions in my understanding about the ways to provide something through a for-profit organization.

If it doesn't exist already, perhaps there can be some sort of foundation whose goal is to fund diagnostics / therapies that start as generics (without a patent)? If immediately offered as generic, perhaps there could be a non-profit donation suggestion at pharmacy or doctor's office (to a foundation that helps develop medical applications without patents)? Or, if this is not quite the right idea, perhaps another possible option that could be up for discussion could be early development in non-profit could translate into decreased time to become a generic (so, even if the non-profit is not directly providing the product with limited profit margins, the contribution of non-profit can still decrease costs to society). This relates in part to an earlier post on obligations to publicly funded research, but I believe my current point is a little different.

There is precedent for the polio vaccine not having a patent, but my understanding that came at a great financial cost to the March of Dimes (and that is why more treatments don't enter the market without patents, even though the fundraising strategy was targeted to a large number of individuals that were already on tight budgets).

Genomics Data and Diagnostics

In "The Language of Life" Francis Collins describes the discovery of the CFTR gene. After describing the invalidation of gene patients for Myriad, he mentions "my own laboratory and that of Lap-Chee Tsui insisted that the discovery of the CF gene, in 1989, be available on a nonexclusive basis to any laboratory that was interested in offering testing" (page 112) as well as saying "I donated all of my own patent royalties from the CF gene discovery to the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation" (page 113).

My understanding is the greatest barrier to having products frequently start out as generics is the cost of conducting the clinical trial. I need to be careful because I don't have any first-hand experience with clinical trails, but are some possible ideas that I thought might be worth throwing out as ideas:

- Allow data sharing to help with providing information to conduct clinical trails. For example, lets say the infrastructure from a project like All of Us allows people to share raw data from all diagnostics (and electronic medical records), as well as archived blood draws and urine samples. Now, let's say you have a diagnostic that you want to compare to previously available options. If the government has access to the previous tests, the original samples, and the ability to test your new diagnostic, maybe use of that information can be combined with an agreement to provide your diagnostic as a generic (with understanding that continued surveillance also serves as an additional type of validation) is a fair trade-off?

- I'm not sure if this changes how we think of clinical trails, but I think participants should also be allowed to provide notes over the long-term (after you would usually think of the trial as ending). This would kind of be like post-publication review for papers, and self-reporting in a system like PatientsLikeMe (which I talk about more in another post).

- Side effects are already monitored for drugs on the market

- Define a status for something that can be more easily tested by other scientists if passes safety requirements (Phase I?) but not efficacy requirements? I guess this would be kind of like a "generic supplement," but it should probably have a little different name.

For some personalized treatments, I would guess you might even have difficulties getting a large enough sample size to get beyond the "experimental" status (equivalent to not being able to complete the clinical trial?). Plus, if some drugs have 6-figure price tags (or even 7-figure price tags), maybe some people would even consider getting a plane ticket to see a specialist for an "experimental" trial / treatment.

Role of the FDA

From what I can read on-line, I believe there is some interest in the FDA helping with generic production, and this NYT article mentions "[the FDA] which has vowed to give priority to companies that want to make generics in markets for which there is little competition", in the context of a hospital producing drugs. According to this reference, "80 percent of all drugs prescribed are generic, and generic drugs are chosen 94 percent of the time when they are available."

Perhaps it is a bit of a side note, but I was also playing around with the FDA NDC Database (which is an Text / Excel file that you can download and sort). For example, I could tell my Indomethacin was produced by Camber Pharmaceuticals by one pharmacy (NDC # 31722-543), and my Citalopram from another pharmacy was produced by Aurobindo Pharma Limited (even though Camber Pharmaceuticals also manufactures Citalopram, and Aurobindo also produces Indomethacin Extended-Release, according to the NDC Database). I thought it was interesting to see how many companies produce the same generic and how many generics are produced by each company. At least to some extent, this seems kind of like how there may be similar topics studies by labs in different institutes across the world. So, maybe there can even be some discussions about how there can be both sharing information for the public good as well as independent assessments of a product from different organizations (whether that be a lab in a non-profit or a company specializing in generics).

I also noticed that the FDA has a grant for "complex" generics, but I believe that is for current drugs that are off-patent but there were extra challenges with production that make offering a generic version more difficult. Nevertheless, it is evidence that there is some belief that academic and non-profit institutes may be able to help bring generics to the market more quickly.

Personal Experience / Open-Source Bioinformatics Software

I believe that I need to work on fewer projects more in-depth. I wonder if there might be value in having a system for independence that would allow PIs to do the same (with increased responsibility/credit/blame at the level of the individual lab). If something entered the market as a generic (possibly from a non-profit), perhaps the same individuals can be involved with both development and production of the generic.

Personal Experience / Open-Source Bioinformatics Software

I believe that I need to work on fewer projects more in-depth. I wonder if there might be value in having a system for independence that would allow PIs to do the same (with increased responsibility/credit/blame at the level of the individual lab). If something entered the market as a generic (possibly from a non-profit), perhaps the same individuals can be involved with both development and production of the generic.

Also, for my job as a Bioinformatics Specialist, I mostly use open-source software (but I sometimes use commercial software or software that is only freely available to non-profits/academics). In particular, I think it is very important to have access to multiple freely available programs, and the topic of limits to precision in genomics methods (at least in the research context) is something I touch on in my post about emphasizing genomics for "hypothesis generation" (at least in the research context).

Concluding Thoughts

Even if is not used in clinical trails (which, as far as I know, was not part of the original plan), I think All of US matches some of what I am describing as a generic from a non-profit (even though it isn't called a "generic," it is a government operation, and free sequencing is not currently guaranteed after sample collection). Nevertheless, non-profit (or academic) Direct-to-Consumer options that I think more people should know more about include Genes for Good (free genotyping), American Gut (can still be ordered from Indiegogo?), the UC-Davis Veterinary Genetics Lab, and I am excited to learn more about others. I think this may also be in a similar vein to DIYbio clubs (for example, I believe Biocurious provides a chance to do MiSeq sequencing). Cores (like where I work) also kind of do this (for labs), but I can tell that I need to work on fewer projects more in-depth (so, I think there would need to be some changes before adopting a "core" model for producing generics).

Finally, I want to make clear that this is something that I would like to gradually learn more about, but that is probably more on the scale of 5-10 years. That is generally what I am trying to indicate when I add "Speculative Opinion" to a blog post title. So, I very much welcome feedback, but my ability to have extended discussions on the topic may be limited.

The only things that I feel strongly about in the immediate future is not reversing the Supreme Court decision to not allow genes to be patented, and the limits to predictive power for some genomics methods (such as the concerns I expressed about the 23andMe ancestry results towards the beginning of this post, and how I don't believe it would be appropriate to encourage travel destinations to specific countries).

Change Log:

5/22/2019 - original post date

-I should probably give some amount of credit for the idea of emphasizing decreased health care costs to Ragan Robertson (for his answer to my SABPA/COH Entrepreneur Forum question about generics and providing something in a non-profit versus commercial setting). However, his answer was admittedly more focused on mentioning how generics could be used for different "off-label" applications after they have entered the clinic (as well as connecting this to decreased health care costs).

5/23/2019 - update some information, after Twitter discussion

5/24/2019 - trim out 1st paragraph

5/25/2019 - move open-source software paragraph towards end. Also, lots of editing for the overall post.

5/26/2019 - remove sentence with placeholder for shared resources post that is currently only a draft. Add link to $2.1 million drug treatment tweet (with every interesting comments)

6/1/2019 - remove the word "their" from 23andMe travel sentence

6/27/2019 - update content in response to discussion with family member. For example, I don't think I was making clear that I was primarily concerned about data sharing / transparency and continuing to not allow genetic testing / information to be patented, at least in the field of genomics (and I am curious if being a non-profit can play a helpful role if those requirements are met).

6/28/2019 - revise explanation for the previous change log entry

6/29/2019 - bring up tax details

7/13/2019 - add explanation for "Speculative Opinion"

7/30/2019 - add comments for Francis Collin's CFTR gene discovery

11/3/2019 - add "speculative opinion" tag

5/6/2020 - minor changes

6/27/2019 - update content in response to discussion with family member. For example, I don't think I was making clear that I was primarily concerned about data sharing / transparency and continuing to not allow genetic testing / information to be patented, at least in the field of genomics (and I am curious if being a non-profit can play a helpful role if those requirements are met).

6/28/2019 - revise explanation for the previous change log entry

6/29/2019 - bring up tax details

7/13/2019 - add explanation for "Speculative Opinion"

7/30/2019 - add comments for Francis Collin's CFTR gene discovery

11/3/2019 - add "speculative opinion" tag

5/6/2020 - minor changes

8/22/2020 - add a couple additional links

10/4/2020 - add FDA "complex" generic grant link + minor changes + add section headers